“TURN HIM TO ANY CAUSE OF POLICY, THE GORDIAN KNOT OF IT HE WILL UNLOOSE FAMILIAR AS HIS GARTER”

—SHAKESPEARE, HENRY V

At the center of an ancient city in an ancient land stood an ancient cart tied with an ancient knot. The cart once belonged to King Gordius, a poor farmer who became a great ruler.

For generations, this cart stood in the city of Gordius as an offering to the gods. Its yoke was tied to a post with what one Roman historian later described as “several knots all so tightly entangled that it was impossible to see how they were fastened.” A prophecy foretold that any man who could unravel this Gordian Knot was destined to become ruler of all of Asia.

Many men tried. The strongest among them would pull with all their might and leave dejected. The smartest would devise brain-bending schemes to loosen it and fail.

When Alexander the Great arrived at the city of Gordium in 333 B.C., he became fascinated with the knot. After wrestling with it to no avail, he stepped back from the gnarled mess and declared, “It makes no difference how they are loosed.” He then drew his sword and sliced the knot in half. Fulfilling the prophecy, Alexander conquered most of the known world.

More than 1,000 years later, one of the earliest appearances of the Gordian Knot in popular culture came in the context of politics. Shakespeare’s titular character in Henry V is praised for his ability to “unloose” the Gordian knots of policy.

Think tanks, nonprofits, political parties and other impact organizations encounter these knots every day. In the face of their complexity, many focus on developing the most logically sound arguments, sophisticated research methods or effective fundraising tools.

But whatever their aim – whatever the composition of their “knot” – every change-maker must ultimately compete for attention, elicit an emotional response and compel action. Effective content cuts the knot. And Bill Gates crowned it king.

In his prophetic 1996 essay, “Content is King,” Gates laid out the case for why content would be where much of the real money was made on the Internet, just as it was in broadcasting:

I expect societies will see intense competition … in all categories of popular content – not just software and news, but also games, entertainment, sports programming, directories, classified advertising, and online communities devoted to major interests…

If people are to be expected to put up with turning on a computer to read a screen, they must be rewarded with deep and extremely up-to-date information that they can explore at will. They need to have audio, and possibly video. They need an opportunity for personal involvement that goes far beyond that offered through the letters-to-the-editor pages of print magazines…

Those who succeed will propel the Internet forward as a marketplace of ideas, experiences, and products – a marketplace of content.

This Lab Report describes a strategy through which organizations can create effective content that wins in the marketplace of ideas. It’s also a lens through which organizations must understand the appeal of their competitors’ messaging and craft an equally compelling counter.

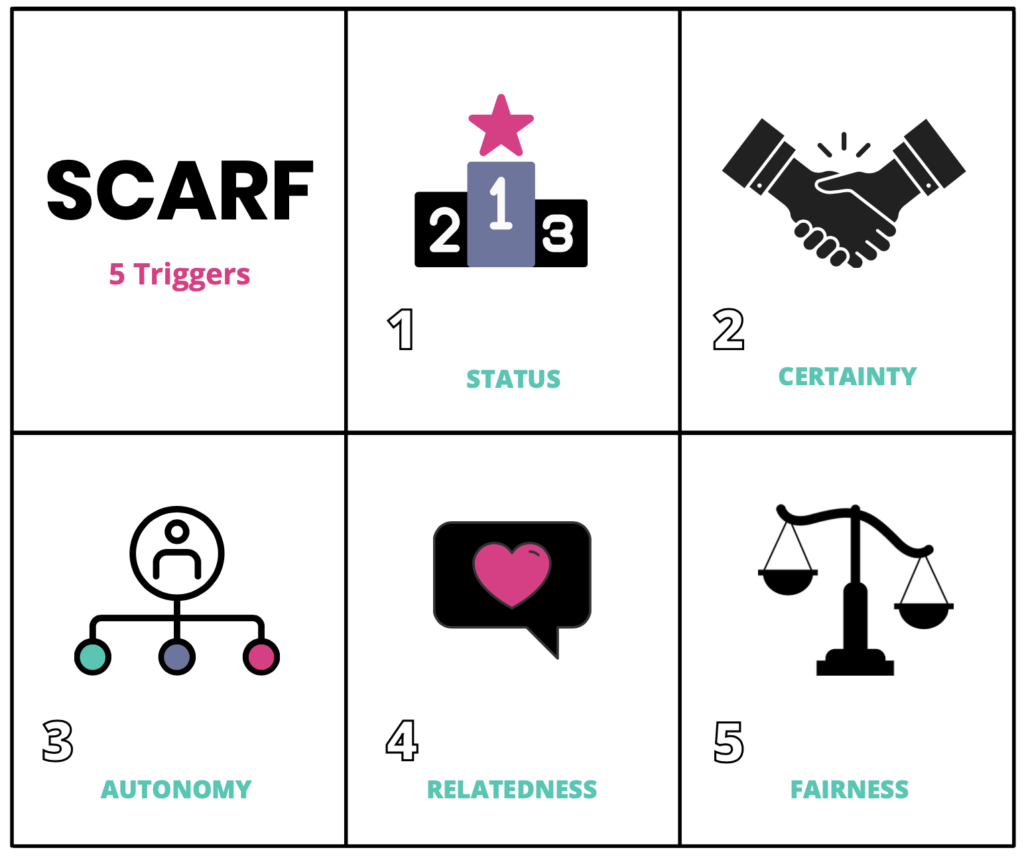

The SCARF model is an acronym for the five triggers of an approach or avoid (fight or flight) response in individuals: Status, Certainty, Autonomy, Relatedness and Fairness (Rock, 2008). The most compelling content grabs attention and compels action with one or more components of SCARF.

Status is all about our relative importance to others. Think about it like pecking order or seniority. If you perceive a status threat, similar neural networks are activated as a threat to your life. If you are left out of an activity, the same regions of your brain light up as if you were in physical pain. University College London Prof. Michael Marmot has argued with compelling research that even after controlling for education and income, social status is the most significant contributor to longevity and health.

Oftentimes in the public policy space, researchers are told numbers and white papers don’t change minds. But one of the most prominent social movements in modern American history, Occupy Wall Street, was based on a figure. “We are the 99%” was the unifying slogan of the Occupy movement, and its brilliance lies in the fact that our brains use similar circuitry for thinking about status and processing numbers.

Humans crave patterns, and pattern-recognition is key to our survival. Without it, we expend far too much energy to complete simple tasks. Even a trace amount of uncertainty can generate an “error” response in the orbital frontal cortex. And the brain fires off these error messages when someone is acting incongruously or untruthfully. Conversely, creating certainty and meeting expectations gives our brains a dopamine hit.

“In these uncertain times” wasn’t just a COVID-19-era advertising meme – it was central to much of the political messaging in favor of continued lockdowns and school closings. Long after research had shown interaction outdoors and in schools was exceedingly safe, invoking even a trace level of uncertainty was enough to keep large swaths of parents from sending their children into classrooms and give cover to politicians closing playgrounds, beaches and parks.

Autonomy involves the sensation of having choices and wielding control over our environment. This sense of control is so important that it alone has been shown to correlate with improved health outcomes (Rodin 1986). In fact, simply viewing a given stressor as escapable, rather than unescapable, can have a major effect on our ability to function. (Donny et al, 2006).

A recent proposal from United States Secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg to tax Americans by the number of miles they drive was quickly shelved after substantial blowback. A similar 2019 proposal in Illinois was not only tabled but wiped from the legislative record entirely after extraordinary backlash from the public, including the sponsoring legislator’s own grandmother confronting him in the grocery store about the bill. Why? Researchers have long shown that car ownership is about much more than transportation, but a sense of independence, agency, autonomy and escape. It’s no wonder that a proposal to install a government transponder in one’s car that tracks and taxes each mile driven generates a strong threat response.

Relatedness is all about deciding whether another person is a part of our tribe; friend or a foe; in-group or out-group. This is why picking the correct messenger to deliver your message is incredibly important – research shows that we process information coming from people we perceive as similar to us through similar circuitry used for thinking our own thoughts, and that this phenomenon does not happen with people we perceive as foes or competitors (Mather, 2006). Even discussing something innocuous like the weather can release oxytocin and increase our feelings of closeness and trust with another person (Zak et al, 2005). Storytelling is especially powerful in the domains of relatedness and fairness.

One of the most impressive uses of relatedness in storytelling and political messaging is “Tenemos Familias (We Have Families),” a short documentary produced by the Bernie Sanders campaign in 2016. Unlike traditional candidate advertising, Sanders does not appear until the third act, long after the viewer has formed a deep emotional connection with the main character’s role as a worker and mother.

Political dissidents across the world have risked their lives in righteous fights against unfairness and injustice. Unfair exchanges can activate a part of the brain called the insular cortex, which is involved in intense emotions such as disgust, and generate a strong threat response. Perhaps most notably, people who perceive others as acting unfairly not only fail to feel empathy for them if they are in pain, but can receive a reward response when the unfair actor is punished (Singer et al, 2006).

In a crime of desperation on behalf of her infant daughter, Lisa Creason attempted to rob a Subway sandwich shop when she was 19 years old. She served one year in prison for her crime. After leaving prison she turned her life around, started a nonprofit combatting violence in her community, raised three children on her own after her fiancée was killed by a stray bullet, and worked full-time as a nursing assistant. In order to provide a better life for her children, she enrolled in additional schooling to become a registered nurse with higher pay, and after years of work passed all of her classes with flying colors. She was then told by the state that she could not legally apply to become a registered nurse due to the crime she committed more than two decades earlier. Even the most ardent Blue Lives Matter supporter would find it difficult to argue that what Lisa experienced was fair. Her story inspired grassroots support across the political spectrum in her home state, including in the law enforcement community, and took the form of a 2017 bill signed by a Republican governor that opened up the field of nursing to tens of thousands of ex-offenders like her.